La Isla Nena

By Melissa Alvarado Sierra

The amapolas fell whenever a strong breeze shook the trees, the scarlet blossoms dropping unhurried like feathers and dotting the vast green floor. My wooden house was nearby; I could see the shanty zinc roof and the white and pink facade through the trees. I lived in Barrio Pilon, a small neighborhood tucked away in the mountains of Vieques, also known as La Isla Nena, an island off the east coast of Puerto Rico. Life was painless and undemanding in what many would call the definition of paradise. Everyday, I took a nap in the jungle, on a bed of green grass sprinkled with amapolas. Pilon was unspoiled, quiet, and seductive. Eternally humid, this rural place was canopied by dense greenery in the form of bamboo, palm, and flamboyant trees. The jungle smelled of coconuts, mangoes, starfruit, and bananas. Pilon felt like a made up place, and I felt like a better person than before I moved there. A little lighter, a little bolder, a lot happier.

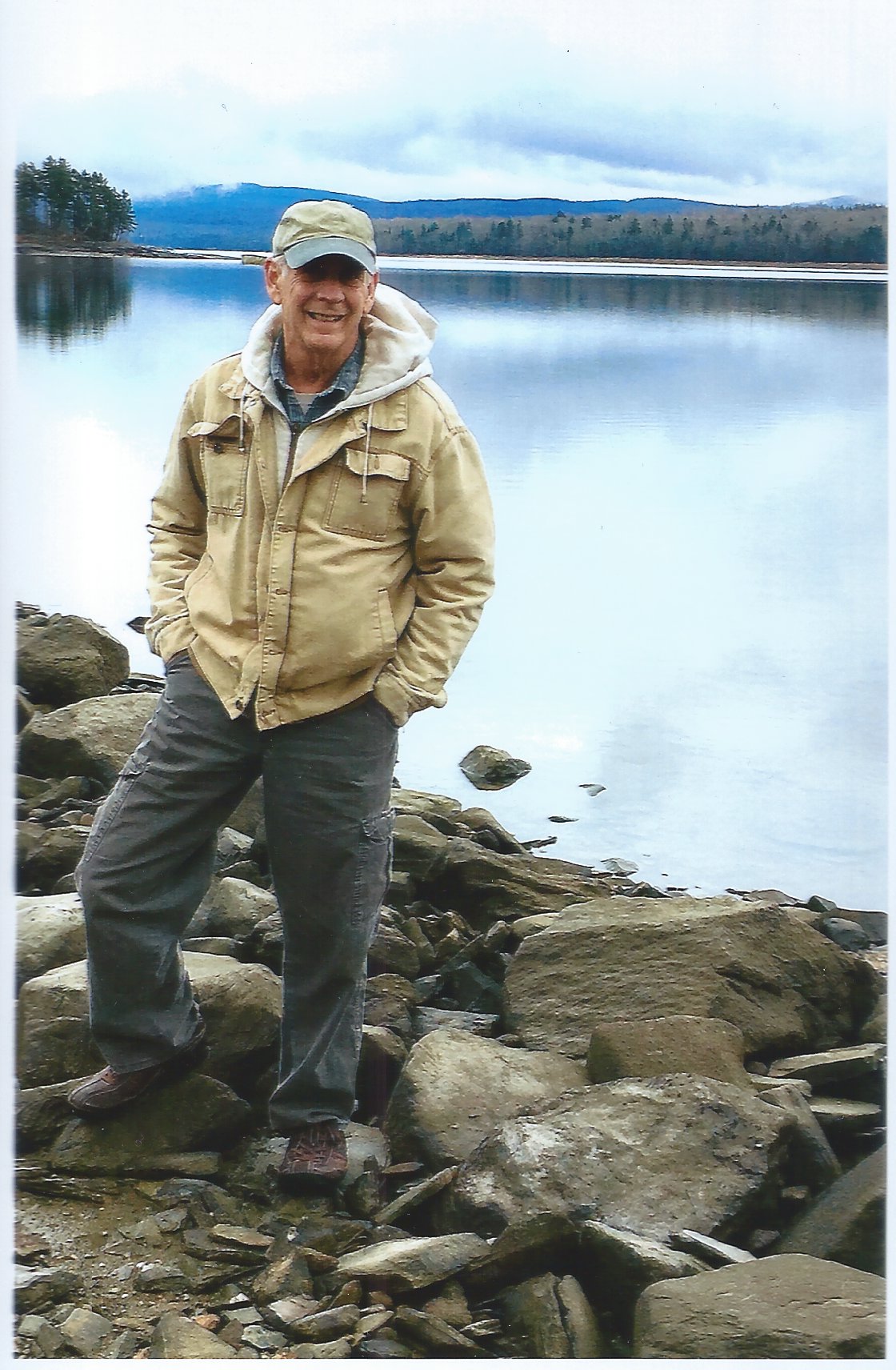

Melissa walking in the jungle of Vieques

I remember sitting within the jungle with a woven basket next to me. The basket was full of fruit I had picked from the trees. I nibbled one end of a starfruit to make a small hole and then ate the pulp, seeds and all. Starfruit juice dripped from my mouth down to my clothes and I didn’t care. I was in Vieques, not in the busy city of San Juan, where I used to live. There was no right way of eating fruit in Vieques. I spent my days in the island like that—wildly eating nature’s sweets, my ears romanced by tropical sounds—mostly of the insistent coqui frogs. Ko-kee, ko-kee, went their song. Tradewinds blew from the east and the overreaching flora fanned everything below. Vieques, my sizzling Eden, was reachable by a faulty ferry or a teeny and decaying plane, which made for a slightly treacherous and vomit-inducing journey. Once there, though, all travel and life traumas faded away.

Vieques’ beaches were tinted with cerulean and turquoise, and the sand was so white and bright it hurt my eyes. But the ocean floor on the east side was sticky with toxic phlegm and the sand of the southeast was covered in putrid radioactive waste. Undetonated bombs lied below the waters and within parts of the jungle. The air was sick and made locals sick—with cancer, immune disorders, neurological diseases. La Marina, the Navy, arrived in Vieques in 1941, settling to test bombs in La Isla Nena. It didn’t matter to them or to the local government when people in Vieques started to die because of it. They kept testing their bombs for more than sixty years.

A map of Vieques with the location of the bombs at El Fortín de Conde Mirasol Museum

In 2011, when I moved to Vieques, I knew little about the contamination. But neighbors told me to stop eating the fruits from the trees. They said the Navy had used depleted uranium, Agent Orange, arsenic, lead, mercury, cadmium, white phosphorus and napalm on Vieques. The traces were found by local scientists on the leaves, within the soil, floating in the water and in the hair of residents. I couldn’t digest something so atrocious. I searched for those allegations and found the Navy had conceded to using the heavy metals and toxic chemicals, but had denied any links to the elevated rates of disease and mortality on the island. Five million pounds of munitions were detonated between 1945 and 2003, and the Navy said it had no effect. Trying to prove otherwise is almost impossible. The Department of Interior owns the land the Navy used to bomb, consisting of two-thirds of Vieques. They restrict access, and so we are in the dark about the real state of the island’s health. They now call the bombed area a “natural reserve.”

Painting by Kayra, A local artist

When the doctor said I had a rare type of thyroid cancer a few years later, I immediately thought of Vieques. I had lived on the island for less than a year, but while I was there I grew increasingly sick. My neck grew bigger by the day, and a strange and dull pain became my normal. I remember the neighbors telling me to stop eating the starfruit. They said the soil was poisoned. But I was so enamored with the singular beauty of Vieques that I ignored what had happened years before. I kept eating the sweet fruits, kept bathing in the beaches, and kept breathing the salty air. Maybe I had been poisoned. Maybe I’m one more on a long list of people who claim the island’s toxicity is to blame for their health issues—that the Navy is to blame. It can’t be proven.

Viequenses believe the cleaning efforts by the Department of Interior have been inefficient. There’s also no serious interest in studying the unusually high cancer rates (27% higher than in mainland Puerto Rico). People are dying. When I flew to Vieques mere months after Hurricane Maria, I found the island to be in very bad shape, but the people were in even worse condition. Cancer patients like Laura, a bed-ridden woman in her sixties, couldn’t have access to chemotherapy and had given up on being cured. Others made the uncomfortable ferry trip to Puerto Rico to find help, but found the journey too arduous to repeat. An oncologist with a focus on natural medicine from the main island, Dr. Marcial Vega, told me he had been voluntarily traveling to Vieques for years to help cancer patients for free because no one else is doing it. There’s no support from municipal, national or federal government. People died after the hurricane, but many more had been dying from the lingering poison. Vieques and its people have been forgotten by all, even fellow Puerto Ricans. Vieques is now known as la isla enferma.

Photo of Protesters in Vieques, asking the Navy to leave the island. They left in 2003.

I’m still not officially cancer-free, though tests have been negative for the past three years. Being relatively healthy again is freeing, but I also have a strange mix of guilt and nostalgia when I think of Vieques. After the hurricane, I sailed to Vieques and drove to the jungle in Pilon, where I used to live. I sat on the ground, this time with no grass and no fruit trees around me. The hurricane took them. I thought about the amapolas from 2011 and how maybe paradise made me sick. I thought about the island as it is today, still sick by the man-made poison that is glued to every leaf and infused into every drop of ocean water. Hurricane Maria made sure this was not forgotten. The winds stirred the old toxins that were hiding within the soil and interred in the depths of the sea. There’s now more proof of contamination. The poison was agitated and released once again. The dirty secret just can’t stay away.

Melissa Alvarado Sierra is a current degree candidate at The Mountainview Low Residency MFA in Fiction and Nonfiction.