AUTHOR’S NOTE: This story is about my brother. Out of respect for his wishes, I’ve chosen not to use his name in this piece.

My brother is schizophrenic. He hears voices. When their whispers began inside his skull, it was like they took turns carving up his grey matter with a serving spoon. He’d forget to feed himself. He’d forget to bathe. He wouldn’t sleep for days, and then when he did, he’d wake up in angry fits of paranoid delusions.

I watched the disease erode him, wash away pieces of him, stone by stone. His illness left a perfectly sibling-shaped hole inside me—a cartoon silhouette of my brother’s body punched through my abdomen.

I called him this Thanksgiving, like I do every year. When I first heard his voice through the receiver, I cringed.

“How are you?” I asked.

“I’ve decided to look into our family history,” he said. “Joined the Buchannan’s Scottish genealogical society.”

“Oh,” I said, “that could be interesting.”

“I gave them my first and last name, but when the guy wanted to swab my cheek, I told him no way. I don’t need anybody cloning me.”

On the other end of the phone, I squeezed my eyes shut, pinched the bridge of my nose between my thumb and finger. “You don’t have to give them your DNA.”

“Yeah, well I’m not going to,” he said, “I’m already afraid of what they’re going to find in our family history, because what if all they find are fucked up people like me?”

My stomach tightened as he spoke. I wanted to tell him that he wasn’t fucked up, that he didn’t have anything to be ashamed of or fear, but instead all that came out was: “I’m sure it will be fine.” As soon as the words left my lips, I regretted them. They sounded insincere. Vapid.

“Whatever,” he said.

A moment of awkwardness between us.

It was my brother that spoke first. “Are you safe?” he asked.

“Sure.”

“Keep a hammer next to your door,” he said. “In case they find anything in this genealogy thing, you should be ready.” There was a beep as he hung up the phone, followed by empty silence on the other end of the receiver. My hands trembled as I ended the call and let a wave of grief roll over me.

My brother wasn’t always like that. Most days, I tell myself I can’t recall what he was like before his illness, but that’s not true. I remember him as he was when we were boys: fearless, rebellious, and endlessly fucking cool.

When he was in fifth grade and I was in third, we used to ride the same bus home together, number 752. We’d sit in the back-back with some other boys, fold up paper airplanes out of our homework. My brother always creased the wings up like a fighter jet.

We’d sit and wait for the driver to haul the bus over the freeway, and at the very peak of the bridge, we’d yell “Bombs away!” and send our worksheets sailing out the windows. Then he and I would exchange giggles, reveling in a shared sense of euphoric vandalism as we watched our squadron glide over the railings of the bridge and cruise over afternoon traffic, crash-landing somewhere out of view on the asphalt far below.

My memory of him on the bus is crisp like a snapshot—his open-mouthed cackle as we send our worksheets out over the warm draft of the freeway, me with my first two knuckles stuffed between my teeth in an effort to contain my excitement.

*

One day, the bus driver, a woman with stiff greying hair, got sick of our antics and stopped 752 on the other side of the bridge. My brother turned to me as she marched her way down the aisle. “Don’t say anything,” he told me, just before her presence loomed overhead.

“Who threw that?” she said. Her gaze was a searchlight in a prison yard, bearing down on unruly inmates. I didn’t dare look at her; I knew my face would betray us. Instead I watched her shadow in the sunlight as she swung her head over the tops of the brown, faux leather seats.

When no one answered, she spoke again. “I’ll write you all up,” she said. “Suspend every last one of you.”

“We didn’t do anything,” my brother said. Out of the corner of my eye, I saw my him square his jaw.

“You threw those planes out the back,” she said. I pressed my knees together in an effort to keep them from quivering.

“Nope,” my brother said. “Wasn’t us.”

“I saw you!”

“Couldn’t have,” my brother said, “because we didn’t do it.”

“I don’t—” the bus driver stopped midsentence. “I saw it in the mirror, paper airplanes zooming out through the window.”

“Did you see who threw them?” He cocked his head to one side, a perfect imitation of a concerned citizen.

“I saw them flying out of the back of the bus.”

My brother shrugged and shook his head.

“Don’t bullsh—” the driver held up a hand. “I’m writing the principal.” She turned on her heel and made her way to the driver’s seat, muttering under her breath. As soon as she sat, she shifted the rearview mirror so that its reflection squared perfectly on my brother. Then she started the ignition. For the rest of the ride, the gaze of the bus driver’s hazel eyes watched my brother in the extra-wide rearview mirror. My brother calmly returned her glare, his hands tucked in his pockets, one leg sprawled lazily across the center aisle, until we got to our stop.

“I’m watching you,” the driver said when the bus pulled to halt and my brother headed to the open door.

He grinned at her as he passed. “Sounds great,” he said, and climbed off the bus, me tagging behind. As he made his way across the street, he shrugged off his backpack, unzipped it and withdrew a folded piece of paper. He turned in the middle of the street and flung his fighter wing down the length of the bus. It soared past the driver’s side window, the 752 stenciled in black, and well beyond the rear wheels. The driver honked, shook her fists. My brother smiled back at her and flipped her a thumbs up before sauntering his way toward our front yard.

*

I know he got in trouble for the paper airplane stunt, but I can’t remember what his punishment was, I guess because the consequences didn’t matter to me. What I remember is my eleven-year-old brother’s smile as he flung his plane, its white edges winking yellow against the side of the school bus—like he was James-freaking-Dean.

I don’t know what the genealogical society will find when they trace our family history. But, Brother, I hope they find a slew of people like you. Brazen, bold, and endlessly fucking cool.

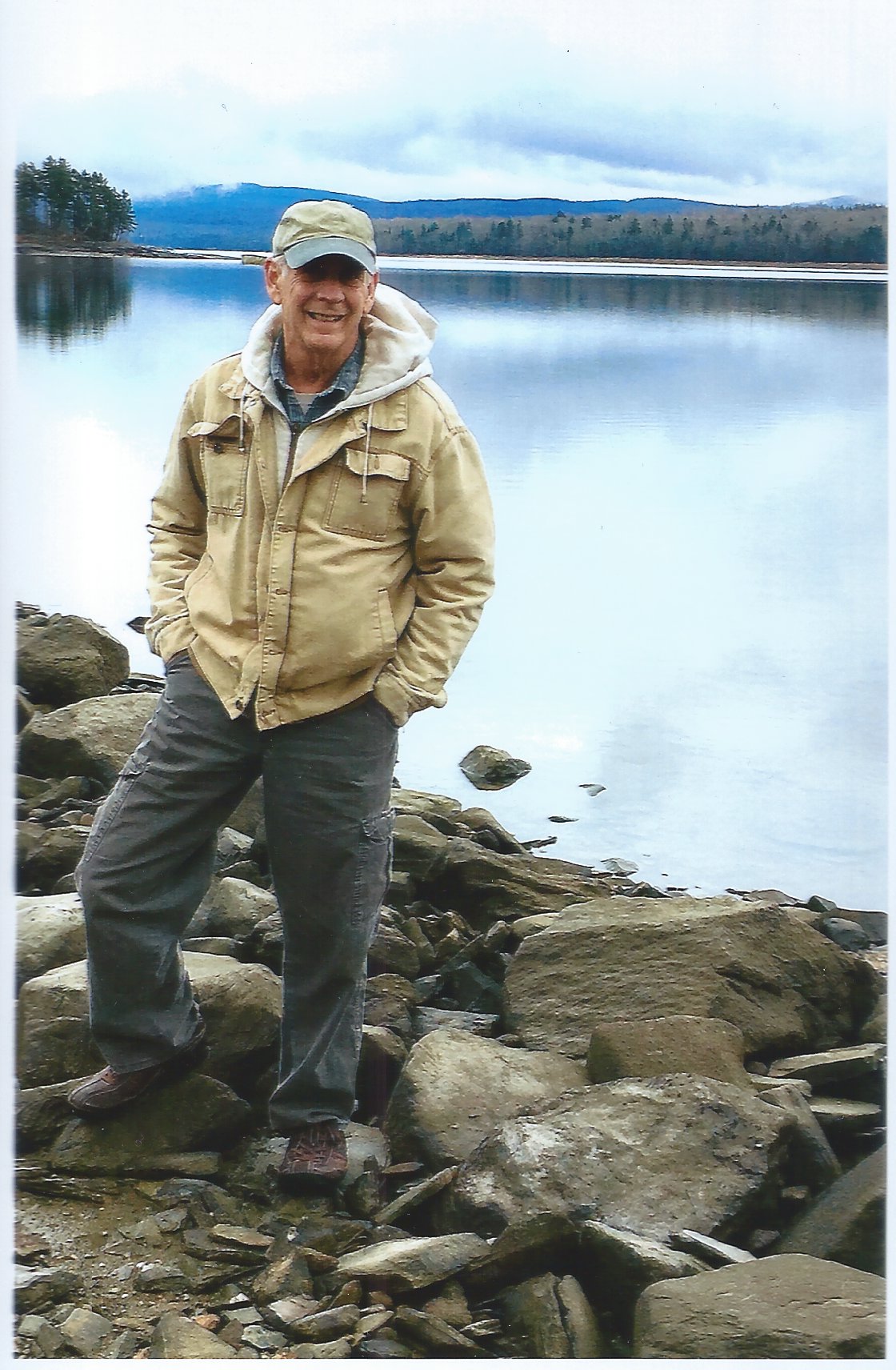

![IMG_3194 (2)[10169].jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/543d9b11e4b0847bb28295dc/1540004690608-QRV6V8P2D0RL3OZRMRQ7/IMG_3194+%282%29%5B10169%5D.jpg)