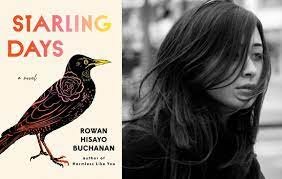

Interview with Rowan Hisayo Buchanan, author of STARLING DAYS

Ed. note: This interview appeared originally in BOMB magazine.

Rowan Hisayo Buchanan is the author of Harmless Like You (2017)—winner of The Authors’ Club First Novel Award, a Betty Trask Award, a New York Times Editors’ Choice and an NPR 2017 Great Read. Critics have praised “Buchanan’s versatility as a writer in her ability to both maintain distance from and be intimate with her characters” (LARB, Ilana Masad) along with the elegance and visceral power of her writing. In her new novel, Starling Days (Abrams), she takes on the story of a young couple, Mina and Oscar, as they cope with the aftermath of Mina’s suicide attempt.

I was drawn to the book not only because, as a psychiatrist as well as a writer, I celebrate rich and questing depictions of depression and other conditions, but because this deft story engages queer desire and identity, family obligation, and idealization versus acceptance in a marriage. I also loved the moral ambiguity and compassion of this book, that deepens the characters and makes the story so engrossing and credible. Finally, the book presents such a fresh take on the “Americans abroad” and “expatriate” narrative, in terms of the sense of dislocation and vulnerability, familiar themes, but in the tech age. In an interview conducted in April 2020 via email, Buchanan talked generously and insightfully about craft, the role of classical myth and tragedy in her work, the influence of nonfiction, and what she has planned next.

--Chaya Bhuvaneswar

Chaya BhuvaneswarHow did you balance honesty and immediacy with an awareness that whatever you wrote was going to "represent" suicidality in some way, especially against the backdrop of the stigma that exists?

Rowan Hisayo BuchananOne of the things that was important to me is that Mina is a specific person—with her own flaws and strengths. I'm not interested in everywoman. None of us are everywoman or can represent an entire group of people. In particular, I didn't want to write a poster-girl for mental illness for two reasons.

A. It's not artistically that interesting to me.

B. I don't think mentally ill people can be reduced to a dichotomy between the hopeless and some Starbucks-perfect corporatized version who perform perfectly despite the sickness. I wanted to write a person who was sick but was also human and as such was sometimes brave and selfless and other times consumed by their own brain.

I tried to write her as a woman responding to her own particular circumstances. As a classicist, she tries to map her feelings onto nymphs, dead princesses, and the women of myth. As a modern woman, she falls down holes of Internet research and Googles her symptoms on WebMD. The journey she takes with her husband Oscar leads her to meet a woman for whom she develops feelings. I hoped that perhaps some readers might be able to relate to Mina's experience but I never tried to portray the Platonic version of depression.

However, I was aware that some people reading this might be in a vulnerable position. So I wrote an author's note addressing those readers who might be considering their own journeys through sickness. I didn't want someone in a fragile state of mind to take some of the cruelest judgments Mina makes about herself to be indictments of their own struggles. I believe fiction should be able to stand for itself without explanation—but I felt too responsible to take that risk here.

Photo of Rowan Hisayo Buchanan by Heike Steinweg.

CBI am struck by the way you found a clear, lovely, dynamic language to represent what can by its nature be a static experience—that of clinical depression. Can you talk about the writing on mental health that has been important or influential for you?

RHBIt is strange to me that depression is so often perceived as being static. In some ways, it might be easier if it were. If the depressed person could just put the whole world on pause while they healed. In some ways, this is the experience that Oscar tries to create for Mina by bringing her on his work trip to London. But unfortunately, this is never the case. Life bites the heels of the depressed person. Mina can feel Oscar becoming fed up. She senses that she is letting her career drift further and further out of her reach. And I hoped to capture that tension.

I think the works of fiction that were most influential to me were simply those that viewed the interior of the mind not as something ghoulish but instead something worth paying careful attention to. To name a few Kokoro by Natsume Soseki which is about love, friendship, and ultimately suicide. Virginia Woolf's Mrs. Dalloway is, I think, unavoidable when writing about intersecting lives, love, attraction to women, and depression. The work of Anita Brookner is not specifically about mental illness but it finds its great drama in the longings and dissatisfaction that occur in the private chambers of her protagonists' minds.

Although for the novel, I read the articles about suicide that Mina does (and more), the nonfiction that most influenced me was about attitude. When I was young, I stumbled upon the work of the poet and psychiatrist RD Laing. I came on his poetry first and then began to pick my way through The Divided Self. The book focuses on schizophrenia. What struck me immediately, was the way in which he did not present himself as being above his patients. He emphasizes that many people "regarded as sane" are equally or more capable of being irrational or dangerous. And while he views his patients as sick he also sees their potential for insight and wisdom.

This is from the 1964 introduction to the Pelican edition of The Divided Self:

A man who prefers to be dead rather than Red is normal. A man who says he has lost his soul is mad. A man who says that men are machines may be a great scientist. A man who says he is a machine is 'depersonalized' in psychiatric jargon. A man who says that Negroes are an inferior race may be widely respected. A man who says his whiteness is a form of cancer is certifiable.

Although there have been many advances in pharmacology since Laing's time, our willingness to ignore the sick or treat their thoughts as being without value seems to remain equally true. Perhaps my greatest desire in this book was to treat the story of the internal fight as worthy as a battle epic.

CBOften as a psychiatrist, I not only treat patients who have suffered from the actions of others--I also treat what legal language calls "perpetrators," people who have raped others, harmed others, terrorized others. Do you feel that duality is relevant to your book?

RHBThank you so much for talking about seeing both sides, because that is especially important to me. As a writer, I’m not very interested in good and evil. They’ve never felt particularly representative of the world. If my characters do something cruel or frightening I want the reader to understand where it is coming from. Most people want to be kind, loyal, responsible and so on. And yet, lovers and family members hurt and abandon each other. For me, writing about trauma and pain is a way of making sense of that.

People talk about emotional baggage, as if it’s something static that we just lug around. I think of our histories as closer to laboratory chemicals. They may be still and silent for years but the addition of a new chemical can neutralize them or make them explode. Mina is born in New York to a Chinese American family who do not have much money at the time. Her mother dies, possibly by accident, possibly on purpose. She is raised by her grandmother who then dies when she is a teenager. She’s put on medication and grows up to be a classicist fascinated by these ancient myths and legends that were supposed to explain the world.

Meanwhile, Oscar is the mixed-race child of an affair. He grows up trying to impress his British friends and his Japanese American father. He’s trying to be successful and normal. And then he falls in love with this woman who tells him she’s mentally ill but has it under control. All of this has already happened by the time Mina’s mental health medication stops working. And the weight of Mina’s loss smashes against Oscar’s need for everything to be okay. It is the collision of these histories that shapes Starling Days.

CBI will be honest and say that I had very mixed feelings about Phoebe, the hot blogger that Mina ends up falling for, and "escaping" with. I actually liked Oscar so much I felt it was disloyal to him to read those sections too closely! Can you talk about Phoebe?

RHBPhoebe was a particularly challenging character to write because she is seen only via Oscar and Mina. Oscar finds her not particularly interesting or noticeable—if anything he is grateful that she is keeping his wife occupied. Meanwhile, Mina is fascinated. She idealizes this beautiful English woman as somehow being perfectly elegant and put together. (Although I think the reader begins to see cracks in this vision. Phoebe is both less perfect than Mina envisions and more vulnerable.) But even Mina wonders if it’s sickness, obsession, a fascination with Englishness or perhaps love.

As the child of an interracial marriage and as a bisexual woman, I am interested in the way our identities shape the power relationships of even the most intimate interactions. There is a section of the book in which Mina follows Phoebe to her workplace. If Mina were a large man this might seem threatening. In Mina’s case it seems tragic or possibly embarrassing. However, there is another layer. As a person who has experienced queer desire but never been able to act on it, she associates a desire for women with unreciprocated pining. I doubt she would follow a man in the same way.

CBTell me about your writing process.

RHBMy own process is a slow one. I write the first draft as a way of learning who the characters are and what their story is. I am not an outliner so this time is exciting. I feel as if I am uncovering something new. Then I edit and edit and edit. This can take two or three times as long as that first draft. In this time, everything is up for grabs. For example, the very first draft of this book included sections written from Phoebe’s perspective. I later cut these because I realized that this narrative worked best when seen from the two sides of the marriage. Then, when I have a second draft that I’m happy with, I print it all out and read it through, marking it up as I go. At times, I’ll read sections out loud to myself or to my partner. Then I send it to my first readers, get their thoughts and begin the editing process all over again.

In terms of advice, I cannot tell anyone how they should write. There is no single correct way. I can say that you should read widely and with an active mind. The width allows you to see what is possible. When you find something you love, it is worth asking yourself why you love it. Is it the structure, the subject matter, the word choices? These become resource banks when you are stuck. Although the majority of what I read falls under that loose title of “literary fiction,” I read poems for language, murder mysteries for structure, and personal nonfiction for the mapping of mental landscapes.

CBHow are you spending quarantine? What are your days like and what are you reading?

RHBI’m mostly trying to keep going with work. I have a little online teaching to do and some longer-term projects that I’m thinking about. I’m reading in bits and pieces—at the moment Tiny Moons by Nina Mingya Powles. It’s about food and identity and language. It also contains some excellent writing about what it is to be mixed race.

I’m also reading Deborah Levy’s The Man Who Saw Everything. I’ve only just begun though so I can’t say if this is a recommendation or not. But I am very intrigued by the choice she has made never to physically describe her main female character but to describe almost lasciviously her male protagonist’s appearance.

CBWhat's next for you?

RHBI hope very much to write another novel. It is in those early tender stages so I’m not sure what it might become. I’ve also been working on some short stories (mostly about ghosts!) that should be coming out soon.